THE CHURCHES OF ST. HELEN IN CROSBY AND SEFTON by Matthew Byrne

Matthew Byrne, a parishioner of St. Helen’s Crosby, has very kindly provided this interesting and informative article for us. Matthew has photographed churches in every county of England and has published illustrated articles on the subject in a number of magazines. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society in 1988 for his work on architectural photography.

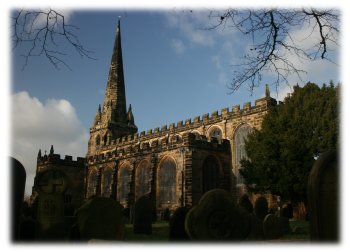

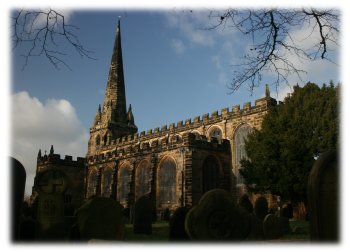

St Helen Church, Sefton

THE CHURCHES OF ST HELEN IN CROSBY AND SEFTON

The Catholic church of St Helen in Crosby has a much older namesake in the area, the medieval (Anglican) parish church of St Helen in Sefton. These dedications to St Helen are common in the north of England. The modern town of St Helens is largely a creation of the industrial revolution in the eighteenth century but its name derives from a medieval chapel-of-ease on the road between Warrington and Ormskirk around which the town grew up. In York, the capital of the northern Church from earliest Saxon times, the thirteenth century church of St Helen presides over St Helen’s Square facing the Lord Mayor’s Mansion House. There are some 160 similar dedications in the north of England, but rarely elsewhere.

Helena (Helen) was the wife of the Roman emperor Constantius who reigned briefly from AD 305 to 306. They were pagan people living in a society where Christians were violently persecuted. Their son Constantine was born in 272 but they divorced in 292. In 306 Constantius was staying in York leading the suppression of a local rebellion at a time when there was much instability within the Roman empire. Constantius died suddenly in York in 306 and his son, Constantine, who was a leading general in the Roman army was declared emperor (Augustus) by his father’s troops in York.

The considerable political and military instability in the empire mean that Constantine had to fight off several rivals for the Imperial crown. A leading rival was Maxentius whose army faced that of Constantine at the battle of Milvian Bridge near Rome on 28 October 312. Before the battle, Constantine is said to have seen the Christian cross in the sky surrounded by the words “In this sign you will conquer.” It is an unlikely story, but Maxentius was defeated and Constantine assumed undisputed power. As a result of this event, Constantine was converted, apparently genuinely, but always somewhat ambiguously to Christianity. In 313, he legalised the Christian religion in the empire by the Edict of Milan and then made it the official religion. Constantine built several large Christian churches in Rome, Jerusalem and Constantinople where he founded an eastern capital of the empire. Christians could now for the first time worship in public.

Helena too, at the age of 60, became a devout Christian and on her travels in Jerusalem is said to have discovered the remains of the True Cross. She died c. 330 in the Holy Land and was buried in Rome. She is venerated in both the Western and Eastern churches. Her feast day is on 18 August. It is because of her indirect connection with York and her pivotal role in early Christianity that so many churches are dedicated to her in the north of England.

To return to Sefton, which like the whole of Lancashire was sparsely populated in the Middle Ages. So, the medieval parish stretched in the north up to Halsall where the medieval church still stands and serves and in the south to Walton church where the medieval church was largely rebuilt in the seventeenth century and again in the nineteenth. All were in the diocese of Lichfield so they could seldom have seen their bishop. Sefton church as we see it today is essentially a late medieval church of the fifteenth century in a style of Gothic architecture known as “Perpendicular.” It is built of a local buff sandstone throughout. The present structure is, however, a rebuilding and extension of a church of the early fourteenth century, the two parts being distinguished by the style of the stone tracery at the heads of the large windows. But the history goes further back. Inside, there is preserved some pieces of stonework whose decoration is associated with the late Norman period of c. 1200.

The Norman church was under the patronage of the Molyneux family who came over from Normandy where they had been millers before the Conquest. The arms of the modern borough of Sefton and of the church are those of the Molyneuxs: a four-armed cross with indented ends which represents a ratchet, part of the machinery of a mill. Their medieval manor house as lords of the manor was immediately south of the church in the triangle of woodland now formed by the junction of the roads to Maghull and Ince Blundell. There were various branches of the family; the main line and cadet branches. The former gained increasing status in society as Viscounts and Earls of Sefton. In the eighteenth century they moved to Croxteth where they built the great Hall. When they left in 1972, the Hall and its park were sold to Liverpool Council which opened them to the public. A cadet branch of the family supplied several rectors for the church in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. When the family moved away from the area it ended eight hundred years of association with the church, a fact commemorated by a handsome modern tablet on the east wall close to the altar.

From the outside, the church is dominated by the large windows which give more glass than stone to the walls on the north, south and east sides. To the west, facing the Punch Bowl Inn, it is dominated by the tall spire which can be seen for miles around across the flat Sefton meadows. At the junction of the spire with the tower below it, there are four curiously stumpy structures serving as buttresses in the shape of beehives. These are a later seventeenth, or, eighteenth century addition to stabilise the tower after damage had been done by high winds.

The principal architectural glories of Sefton church are, however, within its furnishings, principally in the collection of late medieval screens of the time just before the Reformation. There is most prominently the tall rood screen separating chancel from nave. Although there is carving of the most exquisite detail it has the unfortunate effect as far as modern congregation are concerned of separating people from altar and priest at the celebration of the Eucharist. That, however, was the intention of the medieval Church. In addition to the rood screen there are several others separating side-chapels from chancel and aisles. Apart from the quality of the craftsmanship, the screens are significant in the history of art in having several details which turn away from medieval Gothic and point towards the classical Renaissance. There are no furnishings in the whole of Lancashire which surpass the woodwork. The chancel has beautifully carved choir stalls and bench ends of the same time. The altar and reredos are elegant pieces of the eighteenth century.

Although the most prominent members of the parish until relatively recent were the Molyneux family, the Blundells of Little Crosby were prominent and influential from c. 1200 onwards in the parish. (The Catholic church and parish of Little Crosby were established only in 1846). At the time of the Reformation in the 1530s a great rift was created in local society where a large number of Lancashire people clung to the “Old Faith” and refused to conform to the changes of Henry VIII and his successors. These recusants (Latin, recusare, to refuse) included both the Blundells and the Molyneuxs. This did not, however, prevent Nicholas Blundell (“the diarist,” 1669 – 1737) in the eighteenth century having a warm relationship with the Anglican rector of Sefton and holding the office of church warden.

The Catholic, Henry Blundell, of Ince Blundell Hall, also had a good relationship with the church because when he died in 1813, a prominent monument was erected against the north aisle wall. It shows his seated figure surrounded by allegorical groups in the classical style – very appropriate for a man who built up the large collection of classical statuary in Ince Blundell Hall (now in the Walker Art Gallery.)

It is, of course, a source of sadness to many visiting Catholics that they are not at present able to worship in such a noble, dignified and beautiful place. However, ecumenical relations are growing today, albeit slowly, and perhaps, some day, all Christians may be one and able to worship together in the ancient parish churches and cathedrals of England as they did in the past.

Because of the danger of theft (and at the present time, mindless vandalism) the church has to be kept locked outside of service times. However, it is open at various heritage weekends on the summer bank holidays and visits can be arranged at other time throughout the year by contacting the rector or churchwardens.

The Catholic parish of St Helen was created in 1930 from part of SS Peter and Paul parish. The church built at the time became structurally unsafe and was replaced by the present modern building in 1975. There is, of course, less to say architecturally than there is at Sefton. It is a “centrally planned” building in which all members of the congregation are closely associated with the altar and the presiding priests. Over the years, it has become much loved by the people of the parish.

FURTHER READING

1. For more details and many photographs of described above, see Matthew Byrne’s book Great Churches of the North West where a chapter is devoted to Sefton church. (available through St. Helen’s Repository Shop)

2. For the most comprehensive architectural detail of the exterior and interior and of the furnishing, see the South West Lancashire volume of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Monumental Buildings of England series.

PLEASE LET US KNOW IF YOU ENJOYED THIS ARTICLE, BY CONTACTING US Thank You.